About the GPS

In the United States, there are significant opportunities to advance palliative care access and quality beyond the federal level. Recently, there has been a rise in policies on palliative care, many of which have stemmed from increased state-level advocacy by palliative care advocates.

The Solomon Center for Health Law and Policy at Yale Law School and the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) have partnered to create a first-of-its-kind platform tracking legislation on palliative care through the Palliative Care Law and Policy GPS. Established in 2021, the GPS tracks legislation across the 50 states. Data is currently being collected from 2010 to the present.

The first stage of this project focuses on surveying legislation—including enacted laws as well as bills that have been introduced, are pending, or have failed. Subsequent research may expand to cover regulations. Legislation bearing on palliative care policy is organized around eight core categories:

- CLINICAL SKILL-BUILDING: Laws and policies that increase capacity of all health care professionals to (1) initiate meaningful communication with patients about what matters most to them, and (2) provide symptom relief, education, and other services to improve quality of life for people living with serious illness. Examples include clinician training or continuing education requirements in palliative care, pain management, symptom management, opioid prescribing, communication, advance care planning, end-of-life care, caregiver assessment and/or support.

- PATIENT RIGHTS AND PROTECTIONS: Laws and policies that identify access to palliative care as an essential right for people living with a serious illness.

- PAYMENT: Laws and policies that expand financing or provide financing incentives to ensure access to speciality palliative care services or advance care planning. Examples include establishing a palliative care Medicaid benefit, or adding palliative care services into health plan requirements.

- PEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE AND HOSPICE CARE: Laws and policies that support the development and expansion of pediatric palliative care and pediatric hospice (as they relate to access, workforce, quality/standards, clinical skill-building, public awareness, etc.). Examples include establishing pediatric palliative care (PPC) programs, benefits, or standards.

- PUBLIC AWARENESS: Laws, policies, and organizations that promote public awareness of palliative care. Examples include advisory councils, public communication campaigns, information distribution requirements.

- QUALITY/STANDARDS: Laws and policies geared toward developing and meeting quality measures and standards for palliative care. Examples include palliative care definition, measurement of: location of death, use of hospice, advance directives.

- TELEHEALTH: Laws and policies that support the expansion of telehealth to allow delivery of palliative care virtually. Examples include expanding access to telemedicine through changes to face-to-face requirements, reimbursement parity.

- WORKFORCE: Laws and policies that support the growth of a specialty palliative care workforce. Examples include certification programs, loan forgiveness programs, etc.

Palliative care-related legislation is searchable by state, topic, keyword, or status.

The GPS aims to:

- Provide a comprehensive and up-to-date overview of sub-federal palliative care policy

- Allow visitors to analyze how state palliative care policy varies across the United States

- Track legislative trends

- Reveal gaps in legislation and highlight effective policy interventions

- Foster creative approaches to policy innovation

- Encourage policy development, including in historically overlooked communities

About Palliative Care

Palliative care sees the person beyond the disease. It is a fundamental shift in health care delivery.

What is Palliative Care?

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people living with a serious illness. This type of care is focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of the illness. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family.

Palliative care is provided by a specially-trained team of doctors, nurses and other specialists who work together with a patient’s other doctors to provide an extra layer of support. Palliative care is based on the needs of the patient, not on the patient’s prognosis. It is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness, and it can be provided along with curative treatment.

Palliative Care Improves Quality of Life and Lowers Symptom Burden

Palliative care specialists improve quality of life for the patients whose needs are most complex. Working in partnership with the primary physician, the palliative care team provides:

- Time to devote to intensive family meetings and patient/family counseling

- Skilled communication about what to expect in the future in order to ensure that care is matched to the goals and priorities of the patient and the family

- Expert management of complex physical and emotional symptoms, including complex pain, depression, anxiety, fatigue, shortness of breath, constipation, nausea, loss of appetite, and difficulty sleeping

- Coordination and communication of care plans among all providers and across all settings

Numerous studies show that palliative care significantly improves patient quality of life and lowers symptom burden. Apart from being the right thing to do for patients, this improved quality of life also means that an encounter with the health care system is less stressful and traumatic for families.

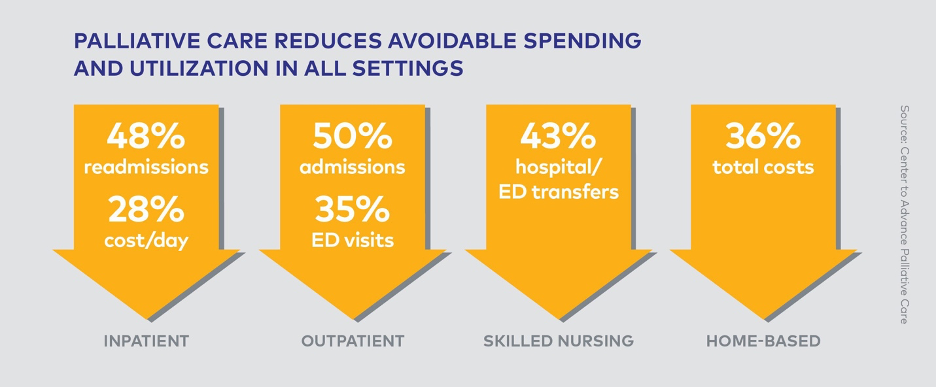

Palliative Care Improves Care Quality While Lowering Costs

Studies consistently show improvements in both quality measures and resource utilization once palliative care is introduced.

The Growth of Palliative Care

The field of palliative care has shown stunning growth over the last 15 years. Today, more than 1,700 hospitals with 50+ beds have a palliative care team, and palliative care is spreading beyond the hospital into community settings where people with serious illnesses actually live and need care.

Glossary

The GPS tracks legislation using several status categories. For the purposes of the GPS, these are defined as follows:

- Enacted: For the purposes of the GPS, this term signifies that a bill has passed into law—most typically by being signed by the governor after successfully passing through the state legislature.

- Failed: A bill that failed to pass in the state legislature or otherwise failed to advance.

- Pending: This refers to proposed legislation, presented in a state legislature after having been drafted.

- Vetoed: Action by the governor to disapprove a bill, preventing its enactment into law.